The divide between religious and secular texts is perhaps most sharply marked by how those texts are treated. Jewish traditions move beyond the study of the word to a veneration of the torah scroll itself which is routinely dressed, paraded, must not be handled and is ultimately buried once it can no longer be used. The theology here is clear; this is the word of God and must be treated accordingly. Moving from this premise, different traditions have read the text in ways markedly distinct from secular reading practices. Most notably, the Kabbalistic tradition has developed modes of reading which appear from the outside to be full-blown lunacy, where meaning is derived by the substitution of letters for numbers according to a variety of seemingly arbitrary methods.

Although it is often difficult to see what can be learnt from the Kabbalists, we could do worse than take from them the idea that when interpreting religious texts, outcomes may be unexpected. Texts sometimes say things that we don’t expect them to and can sometimes have meanings which are far removed from the surface.

All of which is a roundabout way of getting to the main point, which is something like this: There is a failure at the heart of much of Jewish religious practice and belief, and this failure flows directly from an outright inability to read properly.

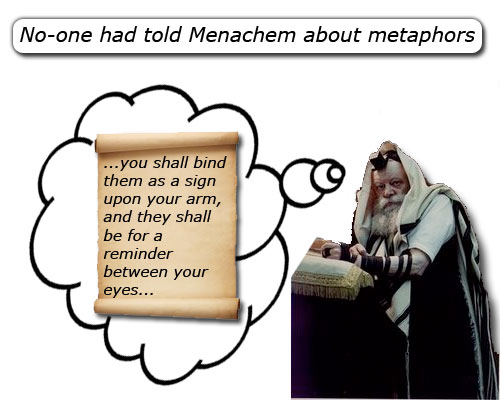

Actually, inability is almost certainly the wrong word; it’s more like a stubborn refusal to read properly. As the above cartoon suggests, much of the problem of interpretation stems from taking things too literally. And this practice is rooted in the divine status of the text, ie if God says it a) He must be serious and b) it must be true. Saner Jews have got round this problem by recasting the text and viewing the torah as a historical document, of its time (which it obviously is). But this does not help the ‘it’s the word of God’ crew who necessarily see the text as timeless and unchanging.

So over the last century, Judaism has divided roughly into these two camps with fundamentally different reading practices. Yet neither side seems to have asked the question Why wouldn’t God use a metaphor?, Or be an unreliable narrator, Or a satirist? Metaphors are the bread and butter of narrative writing. Indeed Lakoff and Johnson have pointed out how we can barely communicate without them. In fact, it is profoundly difficult to read the torah without understanding the use of metaphors.

Let’s start with the first word bereshit, in the beginning. Lakoff and Johnson would jump on this one as an orientational metaphor. ‘The beginning’ is not inside anything. As an abstract noun, ‘beginnings’ cannot be ‘in’ anything. Nor can one be ‘in’ a beginning any more than one can be on, under or next to a beginning. But if we are going to talk about beginnings, we need to situate them and hence we need recourse to metaphors.

But not wanting to split hairs with the hard-to-spot metaphors, what about the great big ones? Sticking to Genesis, creation cries out to be read as a metaphor for a number of reasons. Firstly, it’s a myth. Most religions need a creation myth as a way of thinking about difficult questions like How did we get here? They are far-fetched, fascinating stories, rich in meaning and open to multiple and indeterminate interpretations. What they are not, however, is true. They don’t claim or pretend to be. To read a myth as historical event is simply getting it wrong.

But how do we know that creation is a myth? Well we probably don’t need to look much further than the fact that the torah features two creation myths, one after the other. A major clue that they don’t represent fact ought to dawn on the reader once it is noted that they contradict one another. In the first version, god makes the animals, then man and woman and then rests. The second time around man is made, then each animal and then woman. The text clearly says here, in flashing lights DON’T TAKE ME LITERALLY; THEY CAN’T BOTH BE TRUE. It says don’t worry about the truth of creation, I’m not going to tell you how it really happened. Instead it invites us to ponder the meanings of these contradictory fables. It wants us to ask questions of dominion. Man is clearly given dominion over the animals; he comes both before and after them (and in them if you listen to Rashi), what are we to make of this? Rather than god naming the animals, man does it, why does god allow this? Man and woman are first made simultaneously and then one from the other, what might this mean?

On the other hand, believing that god made the heavens and the earth in six literal days is a fairly harmless belief. It might mark someone out as somewhat foolish, but doesn’t really cause problems of itself. Problems do however arise from other beliefs and practices which stem from other literal understandings of torah. Take the dietary laws. The most well known edict prevents the boiling of a goat in its mother’s milk. A peculiarly specific law, which is followed in a peculiarly specific way by mainstream Jewish authorities; no milk can be consumed with any meat, just in case the law is broken. Yet surely this literalist reading misunderstands wider meaning by which we are supposed to understand compassion towards animals; that animals enjoy relationships between each other, that there are limits to the way in which they are treated and that animals must be treated as individuals, rather than products.

Other unfortunate literal misinterpretations include West Bank settlers’ belief that god gave this territory to Jews alone, the belief that the Jews are the chosen people of god, and a belief that the messiah will come once we keep the commandments properly and rebuild the temple.

So to return to the cartoon, it is an act of extreme perversity to read the lines ‘You shall bind them as a sign upon your arm, and they shall be for a reminder between your eyes’ literally. And indeed in the light of this, anyone wearing tefillin renders themselves somewhat ridiculous by failing to understand the most basic of metaphors. Tefillin thus become a literal sign of the poor interpretation of religious text, of deliberately ignoring one’s own intellect, a type of misunderstanding which leads directly to outrageous actions. All I ask is that before people are taught torah, they are taught how to read.

While we’re on metaphors, how about the metaphor of the rhetorical ‘straw man’?

Case in point: to select only those passages taken literally, and use these passages as a basis to argue that Judaism doesn’t understand metaphor.

You don’t need to be Moses to recall biblical passages not interpreted literally in tradition: e.g. an eye for an eye; do not put a stumbling block before the blind; you shall do no work [on the sabbath day].

To paraphrase: all I ask is that before people are taught how to criticise Torah, they are taught how to read.

What a remarkably poor piece of literary criticism… I expected better from Jewdas.

I’ve never met a serious critical bible scholar who actually views the text as a historical document. It does a remarkably poor job at presenting an account of history.

Moreover, i’ve never met a serious orthodox bible scholar who reads the Chumash literally. Without even needing to get into the details of this issue, anyone remotely interested in Jewish theology knows that orthodox practice is predominantly derived from the mishna and gemorah. The talmud essentialises the orthodox approach to learning – that very little in the five books of Moses can or should be taken literally. There is a valid debate therein of the versacity of the oral tradition, but to base an entire article on the misunderstanding that orthodox Jews read the Torah literally is literally ridiculous.

How on earth did such a laughable piece of writing make its way onto this site?

yes we all know the chumash and orthodox thinking is on the whole exploratory, but the author is right; literalness is the stupidity at the heart of orthodoxy now…and the final frontier is the belief that ‘god’ told settlers they can cheerfully believe the palestinians have no rights. this isn’t a simple piece at all, but a valid comment on an unacceptable hijack of judaism by people who do not read closely or accept the discourse jewish teaching and learning is supposed to embrace. the metaphor of tefillin is a good one,and pointing out the insanity of say, raising pigs on floorboards 6 inches above the earth in israel to counter the halachic prohibition seems like yet another example of how ‘law’ and the haredi mind are sliding downhill..and we should be asking how torah is being taught, and how we read, and whether we’re a living people or a dead ledger with absurd readings of what should be about philosophy and human life.

I wouldn’t take Lakoff and Johnson too seriously. Also, why think true statements represent facts. Consider the following four statements:

1. Scott is the author of Waverley.

2. Scott is the author of 29 Waverley novels.

3. 29 as the number of Waverley novels that Scott wrote.

4. 29 is the number of counties in Utah.

Statements one and two, if they’re about anything are about Scott. Statements three and four likewise seem to be about 29. But statements two and three are near synonyms so can’t be about anything different. But identity is a symmetrical relation so one ought to be about the same thing as 4. It is an argument due to Church, inspired by Frege and developed by Quine, Godel and Davidson among others.